The ‘calculated savagery of the German advance through Belgium’, as described in Croydon and the Great War, had a significant impact on public opinion in Britain as well as being used for propaganda against Germany. The slash and burn style of warfare enacted by German military in Belgium also

caused people to flee. Croydon hosted numbers of Belgian refugees who arrived soon after the war started in the first week of September, with ‘children taken into many Croydon homes’. The Croydon Flag Day in December 1914 raised funds for Belgium refugees. There was a problem, at first, of finding the refugees work but the Belgian government supplied raw materials for carpentry workshops and the Mayor’s Fund gave a small grant. Many of the men were installed in hostels around Croydon town centre.

People were shocked by the atrocities reported in the papers and by Belgian refugees of the German advance through Belgium. The burning of the fourteenth-century University Hall and eighteenth-century University Library at Leuven or Louvain (for more see this site at University of Manchester) made a particular impact. On 25 August 1914, 248 citizens were killed and a sixth of the buildings destroyed including the university library with its medieval manuscripts. The destruction by the German army fed the propaganda of the ‘barbaric hun’ raping and pillaging their way through innocent Belgium. As we now know, the events were sometimes inflated to suit the Allied (i.e. British, French and Russian) cause, though it was based on some truth. Louvain was the centre of intellectual culture in the Low Countries and underlined the importance of Belgium – it was an attack on national pride and cultural heritage. This act convinced many in Britain that British entry into war was justified. This is relevant to talking about air attacks and defences as both international Peace Conventions at The Hague in 1899 and 1907 passed resolutions declaring that:

Aerial bombardment is only legitimate when it is directed against a military objective . . . Aerial bombardment for the purpose of terrorising the civilian population [. . .] is prohibited’ (Hanson, 2008: 20).

Britain signed this accord in 1907 but Germany did not sign either. The German military and government frequently did not understand the international backlash against their actions in Belgium (and elsewhere) as they had signed no conventions and were, as they saw it, applying the rules of war. What the Germans saw as legitimate reprisals, such as the killing of French prisoners of war or killing Belgian or French ‘terrorists’ in the invaded countries, the Allies began to see as ‘terror tactics’ and atrocities that contravened the 1907 Hague Convention IV on Land Warfare (Horne & Kramer, 2001: 175). Isabel Hull has pointed out that the German military saw the treaties around war more as guidance rather than as legally binding and were used to applying brutal methods, as they had done in South West Africa (now Namibia), and ignoring public opinion (Hull, 2005: 129 & 192).

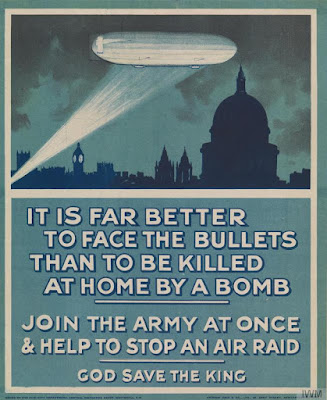

|

French poster, 1918 demanding retribution for German crimes

© IWM (Art.IWM PST 12810) |

Aerial warfare happened within weeks of war breaking out. Antwerp was bombed by Zeppelins on 26 August 1914. Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty and so in charge of British defences, including the Royal Naval Air Service or RNAS) assured Britain that any Zeppelins in our skies ‘would be attacked by a veritable cloud of hornets’. There were not nearly enough planes for such a cloud –the majority of planes and pilots were in any case in France. In September 1914 there was an attempt by the RNAS to attack the zeppelin bases in Dusseldorf and Cologne from Antwerp. In October street lighting was drastically reduced though the full Blackout did not take place until 1915. Britain first experienced a small amount of aerial bombing by a FF29 Sea Plane in Dover on Christmas Eve 1914, followed by fuller assault on Christmas Day through Kent around the estuary area, following the Thames up to Erith and Dartford. Churchill ordered RNAS aircraft to be stationed at Calshot, Eastchurch and Hendon to defend costal and naval ports. Churchill’s successor in May 1915 was Arthur Balfour who stopped the attacks on the Zeppelin bases and commissioned airships, which were ultimately were of little use in the war.

Despite the actions in Belgian, the forays into Britain at Christmas and the urging to do so by senior German military, the Kaiser and Prime Minister of Germany were reluctant to mount air attacks in Britain for various reasons (see Hanson for more). Eventually the Kaiser signed an edict allowing attacks on the east of the Tower of London in May 1915. (The stance by the German political classes changed as the war progressed, or rather didn’t progress on the Western Front, until there was an attempt at a ‘First Blitz’ in 1918.) On 30 May 1915, the day after the Kaiser’s edict, there was a large-scale air raid on North East London: Stoke Newington, Dalston, Stepney and Shoreditch. The raid became infamous as the ‘baby killers’ due to the deaths of young children in residential housing.

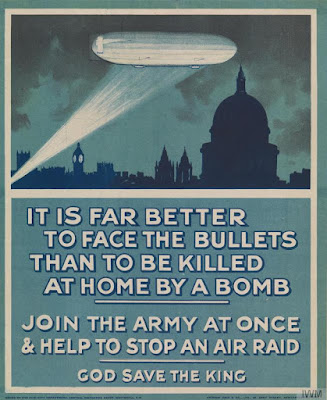

|

| © IWM (Art.IWM PST 12052) |

Zeppelins were a menacing sight in the skies and were reported to stop with no noise causing terror just by their presence. Arguably the action of the German military in both Belgian and air raids inflamed the desire for vengeance at the end of the war, something that the archaeologist Flinders Petrie – based fretfully in London during the war – recognised in a letter to a museum colleague in New York:

But it is a fight for existence out here; Belgium knows it, France knows it, and out people are beginning to feel it at last. It comes near; a friend of mine had his factory (for wood inlaying) burnt out with three bombs, in London. Our miller had his two girls killed by a bomb. Churches have been blown down and streets burnt out; all on civilians far from war affairs. All this will make feeling extremely hard whenever a settlement comes. (Petrie to Lythgoe, 16 June 1915)

Bibliography

De Groot, Gerard (2014), Back in Blighty. The British at Home in World War One, London: Vintage.

Hanson, Neil (2008),The First Blitz. The Secret German Plan to Raise London to the Ground in 1918.

Horne, I and Alan Kramer (2001), German Atrocities 1914. A History of Denial, London: Yale University Press.

Moore, H. Keatley (1920), Croydon and the Great War. The Official History of the War Work of the Borough and its Citizens from 1914 to 1919, Croydon: Public Library

Petrie, W. M. Flinders (1915) Letters to Albert Morton Lythgoe, Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

White, Jerry (2015) Zeppelin Nights: London in the First World War, London: Vintage Books